Robert Poynter, aka Bobby “the Bullet” Poynter, grew up in Pasadena, California, during a time when Mack and Jackie Robinson lived there. Both brothers attended Pasadena Junior College (PJC), now called Pasadena City College. Before Mack’s last year at PJC, he won the silver medal in 220-yard dash in the 1936 Berlin Olympics and Jesse Owens won the gold. Robinson went on to be an active community organizer in the Pasadena area, advocating for civil rights and for safer playgrounds and community centers for children.

The Robinson family, and Mack specifically, were heroes for Poynter growing up. Everyone in his neighborhood wanted to emulate them. Poynter was a well-rounded athlete, playing whatever sport was in season. He and his friends would race each other in the street where he would always finish last.

It wasn’t until the sixth grade he started running as a sport at McKinley Junior High School, where he attended for grades 7th through 10th. It was here he suddenly started winning races against the kids

Bob Poynter in Holland signing autographs after a track meet in 1962.

that beat him when he was younger. He became a track star at McKinley. He finished fifth at the CIF (California Interscholastic Federation) sectional championships in the 100-yard and 220-yard dashes, and he was frequently written about in the local media as an up-and-coming star in track.

He went to Pasadena High School located at the newly named Pasadena City College (PCC) campus, where he won the CIF State Championships in the 220-yard dash as a junior. His senior year, he won the 100-yard dash in the CIF Southern Sectionals and set the State record in the 220-yard dash with a time of 21.0 seconds. (CIF stats, pp. 240, 245)

He started getting noticed by local colleges, such as USC, that actively tried to recruit him. He really wanted to go to USC since it was close to his home. He had the grades, but he didn’t have an academic counselor to let him know which classes he needed to get into the university. USC reps recommended he attend junior college for two years to get those courses.

He attended PCC and became State Junior College champion in the 220-yard and second in the 100 yards. His last year at PCC, he ran for Southern California Striders, one of the best track clubs in the country. He still didn’t have an academic advisor and found out his second year at PCC he still didn’t have the courses he needed to transfer. That’s when he decided to San José State University to train under legendary track coach Bud Winter, moving him to the South Bay where he would later become an assistant track coach at San José City College with Bert Bonanno as head coach.

After six years at City College, he coached at San José State for eight years. He did all of this in addition to being a history teacher, Black Student Union advisor, and track coach at Silver Creek High School in San Jose where he trained and taught future Olympians and City College alums Millard Hampton and André Philips, helped train Caitlyn Jenner, then going by Bruce, in sprinting, among many others who are now coaches around the country.

In celebration of San José City College’s Centennial and the recent Tokyo Olympics, we talked with Bob about his time coaching sprinters at City College and why track is still as relevant as before but not getting the attention it deserves.

How did you get to San José?

After not getting into USC, a friend of mine told me he was going to San José State. I didn’t know where it was, yet Bud Winter had talked to me about coming. My father was going to get remarried to a woman who wanted the house, so I had to find somewhere to go. I called Bud and told him that I wanted to go to San Jose State. Then my friend and I jumped on the bus, sight unseen, and headed to San Jose. We wound up in downtown San Jose at night, not knowing what San Jose was.

Bud Winter was the first real coach I had. He had been a pilot in World War II and studied track in Europe. He was a very, very technical coach, and he was funny. He was like a big farmer. When I first met him, I thought he was some country guy, because he showed up in an old rundown Ford with a gun rack and fishing poles on the car. Yet being so technical, he taught me the basics that I ended up using when I coached. He was a great influence on me and on the track world at that time.

I was one of the founders of Speed City at San José State along with a guy named Ray Norton who was there before me. After I showed up, San José State had two world-class sprinters on the same team who got to compete against each other every day. That was rather unique and got a lot of press attention. San José State started getting noticed. We started getting invitations to run in big meets, like the Penn Relays and others back East where they had heard about us. It put San José State on the map.

1959 was a stellar year for me. I was a gold medalist in the Pan American Games, the NCAA, and a Russia vs. USA meet. We traveled all over Europe. Ray left San José State the next year, but ran for a local club, so he still practiced with me. I had another really good season in 1960, but I never had a year that was so long.

“Because San José was where so much happened in track and field, all of us were very interconnected. I really enjoyed my time at San José City. I call those years the glory years.”

Bob Poynter

I got invited to track meet in southern California called the Compton Invitational. It was about two weeks before the NCAA meet and about three weeks before the Olympic trials. I accepted the invitation, because my family was in southern Cal, as well as my future wife, Gloria, who had gone to Manual Arts High School in L.A. At the meet, I pulled a muscle. You only got one shot back then. It’s not like now where you have sponsors and people managing you, like coaches and nutritionists. So, I was out. I lost the NCAA and the chance to go to the Olympic trials that were held at Stanford. I thought that was the end of my day.

I ran some in 1961, but it wasn’t a good season for me. Then I was drafted. I spent two years on the all-military track team where I won the championships for the whole military in ’62 and ’63. I travelled around the world racing, all over Europe, the Mediterranean and Africa. When I got out, I was able to finish my education with the GI Bill. I soon got married and graduated from San José State.

How did you become a teacher and a track coach?

I was working as a social worker in the Job Corps, when a friend of a college roommate who was also in the Job Corps said I should apply for a teaching job with the Eastside Union School District. Even though I wasn’t looking for a job, I applied, and they hired me in 1969 to teach at Silver Creek High School a month after school had started. I started teaching history, though social science was only my minor at San José State. I learned how to teach as I went!

Soon after, they learned I was a track star and asked if I would coach track. I also started teaching African American history and world history and was the Black Student Union advisor. I had an awful lot of good kids that came through Silver Creek. I think it was really important that they saw an African American male as their teacher. It plays a very important role. You’re a teacher and kind of a father figure at the same time – a mentor.

I first met Millard Hampton in my U.S. History class. He later went to City College and won two medals at the 1976 Olympics. I coached him in track all four years at Silver Creek and wound up coaching him two more years at San José City, so I had him for six years. His father was also a champion athlete. Millard was so talented and played many sports, including football which he was all-American everything his freshman year.

Football is kind of a king sport. Everyone loves it. Millard decided to give up football to run track. I was surprised. The football coach was very upset because he thought I talked Millard out of it. I didn’t particularly care because I was for whatever the kid wanted to do. It was his decision. My thought was, as long as kids were involved, that was good. I also taught the kids my philosophy that if you do something, do it well. They all carried that over into life, and I’m really proud of that.

André Phillips was also one of my kids at Silver Creek. I had him in U.S. history, world history, and African American history. In BSU, we had themed talent shows that were often sold out where both André and Millard developed their public speaking skills. Student-athletes had me a lot which is why we had such a connection. It goes beyond track. Track is just part of it.

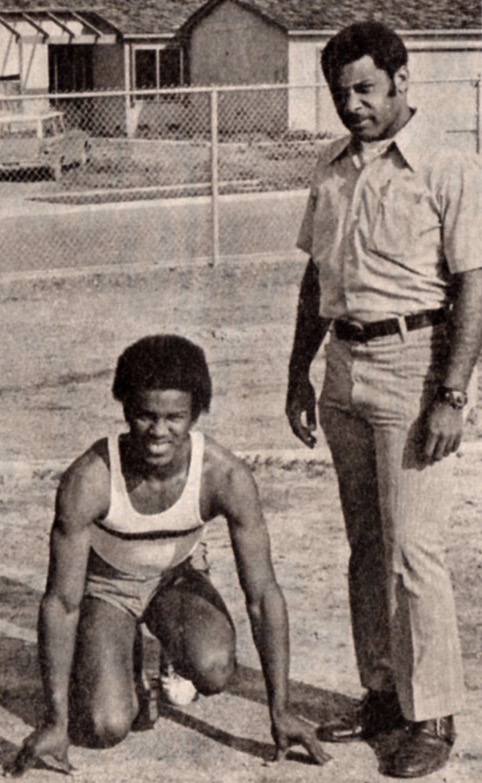

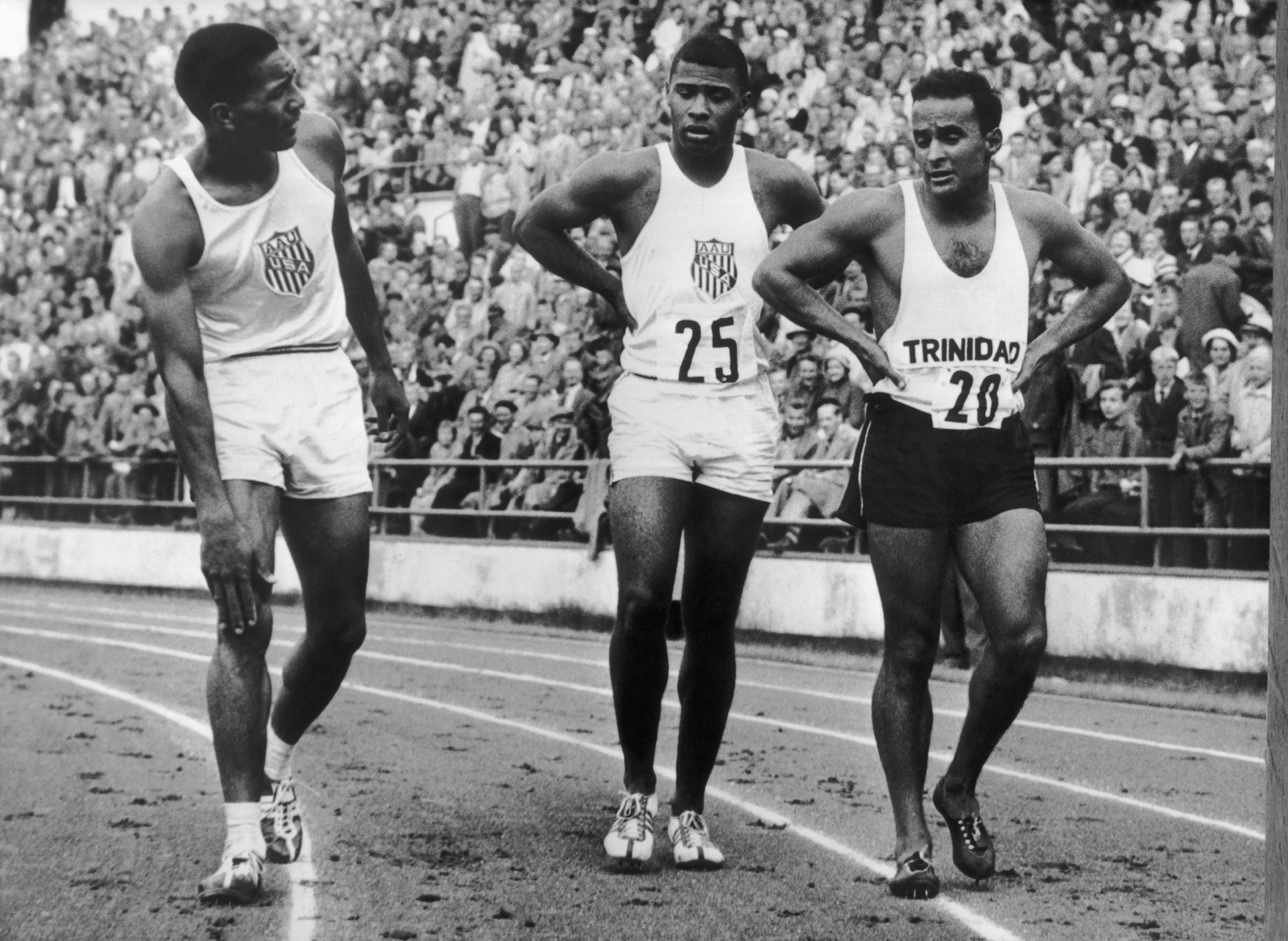

[clockwise from top left] Poynter (right) in Belgium with teammate; Poynter standing next to Millard Hampton at Silver Creek HS; Poynter (center) coaching at Silver Creek HS; Poynter as a part of Speed City at San Jose State; Poynter (center) in Helsinki, Finland, in 1959 with sprinters James Omagbemi (left) and Mike Agostini after running the 100m dash.

When did you start working at City College?

I met Bert Bonanno at San José State. He was the freshmen coach of the national championship freshmen team. He wasn’t my coach since I wasn’t a freshman, but I had known him for a long time. He talked me into coming over and coaching sprinters at City College.

Bert was a great administrator and a great athletics dean at San José City. One thing Bert taught me that carried over as a coach was to surround yourself with good people. Bert knew how to do that. He always had talented assistant coaches around him, which made it nice. Because if you have talented assistant coaches around you, then you’re going to be successful. It’s hard today to find that caliber of coaches.

We had a lot of good people, including our athletic trainer, Arnold Salazar. He just retired and was there for what seemed like 100 years. He played a very important role in keeping the kids healthy. He stayed on top of them and was their support group. He’s a good friend of mine. He really stood out in my life, as a friend, and as a supporter of all the athletes. I look at Arnold as being a very important part of the San José City team.

Bert developed a great physical facility, with one of the top track and field tracks in northern California. The track they have now is largely because of him. He developed a top-quality program that had a lot of class. It was one of the best in the country. All the high school kids – everybody – wanted to come to San José City. City College was the place. He adapted the slogan, Do you know the way to San José, the song by Dionne Warwick, and had that on our uniforms.

Bert and I started the San José Relays, a track and field event that brought in colleges and track stars from around the state. It was extremely successful, and it was later renamed the Bruce Jenner Classic after Jenner won the decathlon at the 1976 Olympics.

At that time, all high school kids took four years of P.E. The high school coaches played a very important role as leaders and role models. Bert developed an outreach program with the coaches and the schools. It attracted everybody in Santa Clara County, plus people who came from San Francisco, Oakland, even from back East like Pennsylvania and South Carolina. We had people from all over who wanted to be a part of track and field at San José City. We received a lot of positive press in the newspapers and on TV because of it. It was a great place to be.

Track and Field was actually larger than the football program at one point. That was all possible because times were very different then. Today, instead of four years of P.E., high school students only have two. P.E. is more a recreation now. Cutting out the last two years of P.E. cuts out your athletic leaders. It has had a devastating effect upon the development of particularly track and field. It’s one of the main reasons there can never be a repeat of what we had at San José City. That’s long gone.

“Track is a sport that should have the most involvement because it involves every event and every type of person. There’s something for everybody…. It’s a participation sport and gender-equity sport with both sexes competing side by side.”

Bob Poynter

Now, where do you discover unknown talent? It was something San José City and San José State did well. Without leadership from high school juniors and seniors, from coaches, it’s impossible. Track is still one of the most popular sports, but you would never know it from the press, because it doesn’t get the coverage that it should. That’s a big problem for the sport, along with football becoming a year-long sport and that there are fewer and fewer people who know how to coach track. Today at an average school, you’re lucky if there’s one person that knows anything about track. Coaches today are “walk-ons”, coming at three o’clock to coach whoever shows up. They have no connection to anything.

Track is a sport that should have the most involvement because it involves every event and every type of person. There’s something for everybody, girls and guys in all the events. Unlike basketball where you only have 12 people, track doesn’t have a set number. It’s a participation sport and gender-equity sport with both sexes competing side by side. What sport does that? I’m glad I grew up in a different time-period than what we have now.

How was it coaching student-athletes at City College?

I got to coach Millard at San José City for two more years, and he wound up making the Olympic Team in 1976 right out of junior college. He surprised everyone. He was this unknown kid who defeated everybody. What were the chances of that? It was because people didn’t know how hard he worked. I was preparing him to be the best, and that’s what he did. He had a team; he had a lot of things in his corner. Millard is a great guy who is very smart and listens. He listened to everything I told him, and he did it. He was willing to put in the work, and that was what it was all about.

Once Bert became the athletics dean, he wanted me to become the head coach and talked to me about getting my master’s for it. I got my master’s at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and interviewed for the job. It was between me and Steve Haas, who came from coaching track at Occidental. They gave it to Steve because he had more experience than me. Steve was a good hire. He had a different coaching style than Bert, but he was a great track coach.

I was going to leave after that, because I had a big commitment at Silver Creek Creek being named Teacher of the Year, being an advisor to 300 kids, coaching; I was overworked and had a family. They had asked if I would work part-time to start the San José City’s women’s track program, since I had started coaching the women the year before because of Title IX. I had the first women’s championships. The women sprinters were my kids, and they were coming back for their second year. I felt really committed to them, so I stuck around until they left.

Women used to have the Girls Athletic Association, a recreation league, and then they turned it into competitive sports. San José City’s women’s teams started around 1978. I had coached a few girls in my life, mostly from Silver Creek for conditioning during the offseason at Hellyer Park. But I didn’t know anything beyond that. I had about five women who started on City’s first women’s track team, including Millard’s sister, Della Hampton. They had never run in competition before. I had to figure out how to train them, and thought, “I’m going to train them just like I trained the guys. I’m not going to show any difference. They are going to have to work just as hard.”

Left photo [from left to right]: Bob Poynter with Millard Hampton, André Phillips, and Bert Bonanno in May 2021; Top right [from left to right]: Poynter’s daughter Adrienne Baines, his granddaughter Avree, and his son-in-law Eric; Bottom right [from left to right]: Poynter’s wife Gloria, his grandson Quincy, Poynter, his son Efferem, his grandson Bobby, and his daughter-in-law Vicki.

They first just wanted to run the 100-meter dash and the 4 x 100m relay. I said, “you came with the wrong guy if you don’t want more than that!” So, I started training them and they started running. Then in their very first year, they won the Northern California Championship and then the State Championship.

And I was shocked because I didn’t know what I was doing. All I knew was that they worked hard. Even today, they still hold many of those records they set in the relays and sprints. I’ve always felt, particularly with Title IX, that women should have equal access to the same things as men.

The next year, they won again. I was very fortunate. I think we got second in one of the relays and we won one of the relays. They were good, and I enjoyed that they transferred to universities, and started getting scholarships. Tina Lawson (Gibbs) went to CSU Bakersfield, Eloise Mallory went to Cal Poly, and Jocelyn West went to University of Oregon. I was proud that they didn’t stop their education after junior college, but they used it as a step to move to the next level. One thing I always told all my track student-athletes was, “track only lasts so long. Make sure you get a degree.”

All those kids could have gone straight into four-year colleges. Most people don’t know that. But they came to City because City was the place to be. Karen Taylor was also on City’s first women’s team along with Eloise, Della, Jocelyn, and Tina. They are some of the student-athletes who made San José City what it was. In addition to Millard and André, I also coached talented sprinters Ernest Lewis, Willye Jackson, Sherman Jones, Ken Merriweather, Fred Harvey, Dwayne Green, Don Livers, Stan Fincher, Eugene Rachal, Tim Foster, Dewayne Taylor, Cecil Overstreet, Jim Douglas, and Horace Berry, among many others who frequently won at state track meets and beyond. All of these student-athletes contributed to San Jose City’s glory years.

What happened after you left City College?

Ernie Bullard, the head coach at San José State, asked me to take over coaching the hurdlers and sprinters for an assistant coach who left. I coached track at San José State for eight years. I only went there because it was my alma mater, and I knew Ernie.

I did this while teaching and coaching my second stint at Silver Creek after my daughter started high school there. I asked Frank Slaton, a track coach teaching at another local high school to be my assistant coach. Together we helped to create the Hampton-Phillips Track Classic that brought in high school track teams from all over the state. It was a big event and was around for ten years.

I later went on to be head coach at West Valley College. I never wanted to do that, because I had other responsibilities. I was an assistant coach at West Valley, and one day they gave me the keys and said, “you’re the head coach.” After ten years at West Valley, I retired. Now, I only train my grandchildren.

I’d like to give some kudos to my wife, Gloria. She supported me all the way, with everything I did. Boy without her, I would not have been able to do anything. She’s a superstar. We happened to meet at a park in Pasadena. She was with a group of people my friend knew. It’s strange, because for some reason I knew she was always going to be in my life, but I didn’t know it would be 59 years! It was a blessing and she’s been really supportive of everything I’ve done. I can’t say enough about her.

“One thing I always told my track student-athletes was, ‘track only lasts so long. Make sure you get a degree.'”

Bob Poynter

I have a son and a daughter. I have two grandkids from my son Efferem and his wife Vicki, and both are in college. Quincy is in his second year at Cal Berkeley, and Bobby is at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, where I got my master’s. Bobby got a scholarship at Cal Poly as a track athlete. He won the Big West Championship in the 800m and graduated in three years. He’s about to start as a graduate student at USC and will be competing on their track team. How about that?!

Efferem is a retired Federal officer who now works for the San Ramon School District as a liaison. He also coaches track at the local high school in San Ramon. My daughter, Adrienne Baines lives in Puyallup, Washington where I have a granddaughter, Avree, in the third grade. My daughter works for the pharmaceutical companies and her husband, Eric, is a chef. I’m blessed! I have the best family.

Being at San José City College was one of the great times of my life. I’ve been involved with and gotten to know a lot of outstanding people, too many to mention everyone, but there are a couple I’d like to note. Gene Neeley was a high school coach who always asked me questions about how to coach track. He observed me and he became a friend of mine. He eventually became the coach for four-time Olympic medalist Ato Boldon. Today Ato is a track and field TV announcer; you may have heard him during the Tokyo Olympics. And Ato is also a San José City graduate.

JoJo Wright was a student I had at Silver Creek and then at City. He’s now a trainer at Louisiana State University. Michael Chukes, who I coached at San José State, ran hurdles at City and is now one of the top sculpture artists in the nation.

Steve Nelson is the current coach at City. He’s a teacher at Mount Pleasant and coaches part-time which is difficult when you’re head coach. He works hard and is very enthusiastic to make it the best program he can.

Because San José was where so much happened in track and field, all of us were very interconnected. I really enjoyed my time at San José City. I call those years the glory years.

Left photo: Poynter’s grandson Bobby on the track with Poynter’s picture in the middle while at San Jose State; Top right (from left to right): Poynter’s family – daughter-in-law Vicki, grandson Bobby, son Efferem, wife Gloria, and Poynter at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo; Bottom right (from left to right): Poynter’s family – daughter Adrienne, granddaughter Avree, and son-in-law Eric.

One thought on “San José City College Centennial: Robert Poynter”